Now onto part three of our week of thinking out loud about putting identity on the blockchain. In part one we found a problem that could be solved using some kind of identity infrastructure. In part two we came up with a model of digital identity that we could use to explore a potential solution to this problem. Now, we are going to think about how that model could connect with some kind of shared ledger in general and with a blockchain or, indeed, the blockchain.

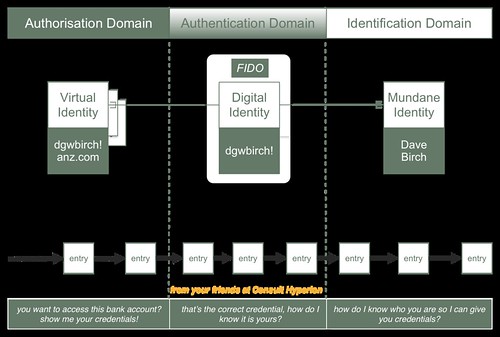

Our starting point is to observe, as my colleague StevePannifer said in his presentation at the Cloud Identity Summit in New Orleans this week, a ledger is a record of transactions. Therefore, we must think about the identity transactions implied by the model that we looked at in part two before we start to think about how to store them in a shared ledger. We start by observing that identity transactions are the “CRUD” (that is the Creation, Reading, Updating and Deleting) of identities. Since our model includes three kinds of identities it admits the possibility of three distinct sets of CRUD transactions that might be stored in the shared ledger as shown in the picture below.

//embedr.flickr.com/assets/client-code.js

//embedr.flickr.com/assets/client-code.js

The first category relates to the mundane identity CRUD of people, things and organisations. We could take some physical characteristic of these such as a fingerprint, a photograph or a serial number and store these in a shared ledger. This may be a good thing to do, but my first thought about this is that actually we probably want to avoid storing such things in the ledger or at the very minimum storing them in unencrypted form. I have to spend some time thinking this through, but it’s not immediately obvious to me that storing the binding between the digital identity and the mundane identity on the ledger moves us forwards.

The second category relates to the digital identity CRUD. Remember from part two that I am imagining the digital identity as being, essentially, a key pair. We need to store the private key somewhere safe and provide an authentication mechanism so that control over the digital identity can be asserted. Then we need to provide the public key for a variety of uses. Now, a key pair sounds very much like a wallet on a block chain and it is certainly a plausible hypothesis that this could be an implementation of digital identity. However it suffers from the same general category of problem as does cryptocurrency, which is the problem of the storage and protection of the private key. Either you have to look after the private key yourself, which is a degree of responsibility that I for one am most unwilling to accept, or you have to trust somebody else to look after the private key for you (e.g. your bank).

In practice, this would mean that the key pair is held by some third-party and while the idea of having sovereign control of your digital identity in some sort of blockchain is an appealing prospect if you are a 20-year-old computer science major MIT, I remain unconvinced that is a mass-market solution especially in developing countries. Here, I feel that the example of M-PESA (as we were discussing on Twitter yesterday) is illustrative. M-PESA, which was launched remember by a telco not by a bank, stores cryptographic keys in the tamper-resistant SIM in a mobile phone and this strikes me as being the plausible mass-market solution. In an M-PESA-like system, the SIM generates the key pair and gives up the public key but the private key is never disclosed. Uunfortunately this means that if you lose your SIM you may have messages that you can no longer read so we need a more sophisticated mechanism for a workable mass-market infrastructure!

The third category relates to the virtual identity CRUD. Remember in the model that I sketched out in part two, I made the assumption that all transactions are between virtual identities. Now the transactions associated with a virtual identity, if they were to be stored in a shared ledger, would then provide a record of that virtual identity’s activities. Those virtual identities need not identify the binding between the digital identity and the mundane identity. So, I could have a digital identity that I use for work and one for home and one for play. I use my play identity to obtain an adult identity from some grown-up website and that identity might well contain attributes that it has obtained from other credentials (that I am over 18, for example) but not my name.

Then the history of that virtual identity is in effect a kind of reputation. If you ask me for my reputation on some sharing economy platform, I can point you to a entry in the shared ledger. This gives you a public key. You can do two things with this key right away. First of all, you can use it to encrypt a challenge for me (because in order to answer the challenge I must have control over the corresponding private key). Secondly, you can look through the ledger to find transactions associated with that public key (to find out, for example, when the virtual identity was created) and whether is has been deleted.

You can also check the digital signature on the virtual identity to confirm who created it (i.e., was it really Barclays Bank or AirBnB or whoever).

The ability to check the reputation of a counterparty in this way seems to me to one of the fundamental benefits of such an identity infrastructure and central to a functioning online economy.

If I find a seller labelled as John Doe, I really have no interest in discovering their underlying identity: that takes time and effort. If there are positive comments about them from people whose opinion I value then I will do business with John Doe. If there are negative comments, then I won’t. And it won’t matter to me whether John Doe has badge from the local council, the government or some other body’s approval. My decision will be based not on what anyone thinks, but on what everyone thinks.

This comes from an article I wrote for “The Guardian” a fair few years ago (“Reputation not Regulation”, 2nd Nov. 2000, sadly longer online but you can download a PDF here). On this, I don’t think my opinion has changed much. The ideas that I was putting forward back then we constructed to support economic activity with both security and privacy as priorities. If anything, my views about building security and privacy into the identity infrastructure have become more entrenched since then.

In the model we’ve been building up this week, then, reputation can be interpreted as the history of a virtual identity, the complete list of “CRUD” transactions stored in the shared ledger. Does this seem like a reasonable model to proceed? If so, tomorrow I’ll think out loud about how to implement the shared ledger for identity.