David Babbs is the project lead for UK-based campaign Clean Up the Internet. The campaign’s proposals argue that everyone on social media should be given a choice to prove their identity. Users could choose whether to see posts from unverified users or not. Crucially, this method of handling anonymity would still enable users who prefer to stay anonymous, to do so. Molly Millar, in an interesting piece about these proposals says that the technicalities of haven’t yet been worked out yet, although they have by me.

What’s critical to a breakthrough in this area is to understand “proving your identity” is not actually the solution and I’ll try to explain why. It’s not a new idea to try to link social media accounts to government-issued identity, as they do in (for example) China. A while back, to pick on one example, the noted entrepreneur Mark Cuban said that “It’s time for @twitter to confirm a real name and real person behind every account, and for @facebook to to get far more stringent on the same. I don’t care what the user name is. But there needs to be a single human behind every individual account”. Politicians think the same way. In the UK, historian Damian Collins MP (chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport select committee in the UK Parliament) said that “I think accounts should be verified, it can’t be right that cowards and racists can hide behind the anonymity of social media to attack people, often using multiple bogus accounts”.

These are real problems, but anyone familiar with the topic of “real” names knows perfectly well that they make online problems worse rather than better. One example that springs to mind to illustrate this is when the dating platform OKCupid announced it would ask users go by their real names when using its service (the idea was to control harassment and promote community on the platform) but after something of a backlash from the users, they had to relent. Forcing the use of real names in a great many circumstances will mean harassment, abuse and perhaps even worse. You can understand why. Why on Earth would you want people to know your “real” name? That should be for you to disclose when you want to and to whom you want to.

In fact the necessity to present a real name will actually prevent some transactions from taking place at all, because the transaction enabler isn’t names, it’s reputations. And pretty basic reputations at that. I think that online dating, frankly, provides a useful way of thinking about the general problem of online identity. In this case, just knowing that the object of your affections is actually a real person and not a bot (remember, in the famous case of the Ashley Madison hack, it turned out that almost all of the women on the site were actually bots) is probably the most important element of the reputational calculus central to online introductions, but after that? Your name? Your social media footprint?

There are plenty of places where I would not want to log in with my “real” name or by using any information that might identify me: the comments section of national newspapers, for example. “Real” names don’t fix any problem because your “real” name is not an identifier, it is just an attribute. This is an important point. Many people who comment on this topic jumble together two quite different issues: proving the account “David Beckham” points to a specific person, and proving that the specific person it points to is the former Manchester United winger David Beckham. The first is about attaching attributes to a real-world entity, the second about is about the reputation of the real world identity. Thinking these two things through separately is, I think, a key to finding a workable solution to the social media mess, but back to that later.

What social media needs, and what will help with Mark Cuban’s actual problem with being sure that there is a “single human” behind an account, is the ability to determine whether you are a known real person or not. The way forward is surely not for Twitter et al to try and figure out who is a disinformation bot and whether they should be banned (after all, there are plenty of good bots out there) but for Twitter et al to give their users the information they need to make a choice. Why can’t I tell Twitter that I only want to see tweets from real people that can be identified?

This is the way to Clean Up the Internet. I don’t want to know the identities — it’s none of my business who a person actually is and it’s none of Twitter’s business either — I just want to know if I’m following a person or not! I know that I’m on the right track here, by the way, because noted entrepreneur Elon Musk agrees with this prescription, having reportedly told Jack Dorsey, the head of Twitter that “I think it would be helpful to differentiate’ between real and fake users… Is this a real person or is this a bot net or a sort of troll army or something like that?”.

So who is the someone who knows whether I am a real person or not? Working out whether I am a person or not is a difficult problem if you are going to go by reverse Turing tests or Captchas. It’s much easier just to ask someone else who already knows whether I’m a bot or not. There are plenty of candidates. There’s the Post Office I suppose. And my employer. Or my doctor. In fact, there are lots of people who could testify to my existence. But the obvious place to start is my bank. So, when I go to sign up for internet dating site, then instead of the dating site trying to work out whether I’m real or not, the dating site can bounce me to my bank (where I can be strongly authenticated using existing infrastructure) and then the bank can send back a token that says “yes this person is real and one of my customers”. It won’t say which customer, of course, because that’s none of the dating site’s business and when the dating site gets hacked it won’t have any customer names or addresses: only tokens. This resolves the Cuban paradox: now you can set your preferences against bots if you want to, but the identity of individuals is protected.

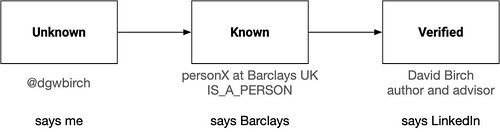

What is crucial here is the IS_A_PERSON attribute.

As Etherum founder Vitalik Buterin said on Twitter (4th April 2020), “proof-of-unique-human” is going to be a very valuable primitive for applications in the years to come.

and Twitter could use this to replace its binary verified-or-not tick system with a much better alternative. Twitter should mark my account as of unknown origin until it sees the IS_A_PERSON attribute. Of course, Twitter will want to see it in the form of a verifiable credential signed by someone who they can sue if it turns out I’m not a person after all, but you get the point. When I sign up to Twitter I am “unknown”. When they get a valid IS_A_PERSON credential from me, then my status changes to to “known”. Once I am known, then I can go on to be verified if I want to be.

Most normal people, I imagine, will leave their Twitter account in the default setting of “known only”. Some people might want to go tighter with “verified only”. This is an important issue that I have been posting about for years, to no avail. Anne Marie Slaughter summed up the situation very well in the FT, saying that “with the decline of traditional trusted intermediaries, and the discovery that social media account holders may well be bots, we will crave verifiability”. This is absolutely spot on, and we need to construct the networks capable of delivering this verifiability or we collapse into a dystopian discourse where no-one believes anything.

The knee-jerk “present your passport to use Twitter” is not the way forward. Technology means that we can deliver verifiability in a privacy-enhancing manner, so let’s do it.