For the first decade or so, it was far from clear whether the credit card was continue to exist as a product at all, and as late as 1970 there were people predicting that banks would abandon the concept completely. Then along came the magnetic stripe. The introduction of the stripe and Visa’s BASE I online authorisation system changed the customer experience, transformed risk management and cut costs dramatically.

(I can’t resist pointing out that it was actually London’s transit authority that pioneered the use of magnetic stripes on the back of cards in a mass market product. Their first transaction was at Stamford Brook station on 5th January 1964, well before BankAmericard introduced their first bank-issued magnetic stripe card in 1972 ahead of the deployment of the BASE I electronic authorisation system in 1973.)

The payment card stripe has had a good fifty years, from then until now, but its days are numbered. Mastercard has announced that the stripe will start to disappear in 2024 from regions where chip cards are already widely used (eg, Europe). The US stripeout will begin three years’ later in 2027, then by 2029 no new Mastercard credit or debit cards will be issued with a magnetic stripe.

The demise of the stripe makes me wonder when the signature will follow. The Daily Telegraph that “written signatures are dying out amid a digital revolution ”. I’m going to miss the stripe and the signatures.When it comes to making a retail transaction, my signature is utterly unimportant. This is why transactions have worked perfectly well for years when I either did not give a signature (for contactless transactions) or gave a completely pointless signature as I did for almost all US card transactions.

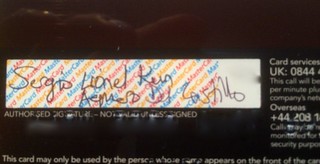

If I do have to provide a signature, then for security purposes I never give my own signature and by tradition sign in the name of my favourite South American footballer who plays for Manchester City. I was encouraged to continue this tradition when I discovered that is constituted sound legal advice. Gary Rycroft, a solicitor at Joseph A. Jones & Co. said “I always sign my initials, for example, so I could prove if it wasn’t me” (because, presumably, a criminal would try to fake Gary’s signature).

Now the issue of

signatures and the general use of them to authenticate customers for credit card transactions in the US has long been a source of amusement and anecdote. I am as guilty as everybody else in using the US retail purchasing experience to poke fun at the infrastructure there (with some justification, since as everybody knows the US is responsible for about a quarter of the world’s card transactions but half of the world’s card fraud) but I’ve also used it to illustrate some more general points about identity and authentication.

Brett King wrote a great piece about signatures a few years ago in which he also made a more general point about authentication mechanisms for the 21st-century, referring to a UN/ICAO commissioned survey on the use of signatures in passports. A number of countries (including the UK) recommended phasing out theme-honoured practice because it was no longer deemed of practical use.

Let’s Ask The Talmud

If you are interested in the topic of signatures at all, there was a brilliant

NPR Planet Money Podcast (Episode number 564) on the topic of signatures for payment card transactions. Ronald Mann (the Colombia law professor interviewed for the show) noted that card signatures are not really about security at all but about distributing liabilities for fraudulent transactions and called signatures “eccentric relics”, a phrase I loved and blogged about at the time.

In addition to the law professor, NPR also asked a Talmudic scholar about signatures. The scholar made a very interesting point about the use of these eccentric relics when he was talking about the signatures that are attached to the Jewish marriage contract, the

Ketubah. He pointed out that it is the signatures of the witnesses that have the critical function, not the signatures of the participants, because of their role in dispute resolution. In the event of dispute, the signatures were used to track down the witnesses so that they can attest as to the ceremony taking place and as to who the participants were. This is echoed in that Telegraph article , where it notes that the use of signatures will continue for important documents such as wills, where a witness is required.

The NPR show narrator made a good point about this, which is that it might make more sense for the coffee shop to get the signature of the person behind you in the line than yours, since yours is essentially ceremonial whereas the one of the person behind you has that Talmudic forensic function. I occurs to me that same is true when I sign for deliveries! It would make more sense for the deliver driver to get a signature from a random passer by then from me, although I suppose now that they have started photographing instead of asking for a signature.

The Talmudic scholar also mentioned in passing that according to the commentaries on the text, the wise men from 20 centuries ago also decided that

all transactions deserved the same protection. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a penny or £1000, the transaction should still be witnessed in such a way as to provide the appropriate levels of protection to the participants. Predating PSD2 by some time, the Talmud says that every transaction is important and requires strong authentication.